Modeling and analysis of patient mechanical ventilation

Mechanical ventilation stands as a crucial medical intervention utilized to support individuals with compromised respiratory function. Employing a mechanical ventilator, this life-saving technique assists or replaces spontaneous breathing, particularly in intensive care units and emergency scenarios. Despite its indispensable role, mechanical ventilation is not without potential risks and complications. Patients undergoing this intervention may encounter challenges such as ventilator-associated lung injury, infections, hemodynamic instability, and notably, patient-ventilator asynchronies. These asynchronies refer to discrepancies in timing, flow, or volume between the patient’s respiratory efforts and the ventilator’s delivery of breath, posing an additional concern that healthcare professionals must carefully address to optimize patient outcomes.

Modeling of the lung-ventilator system

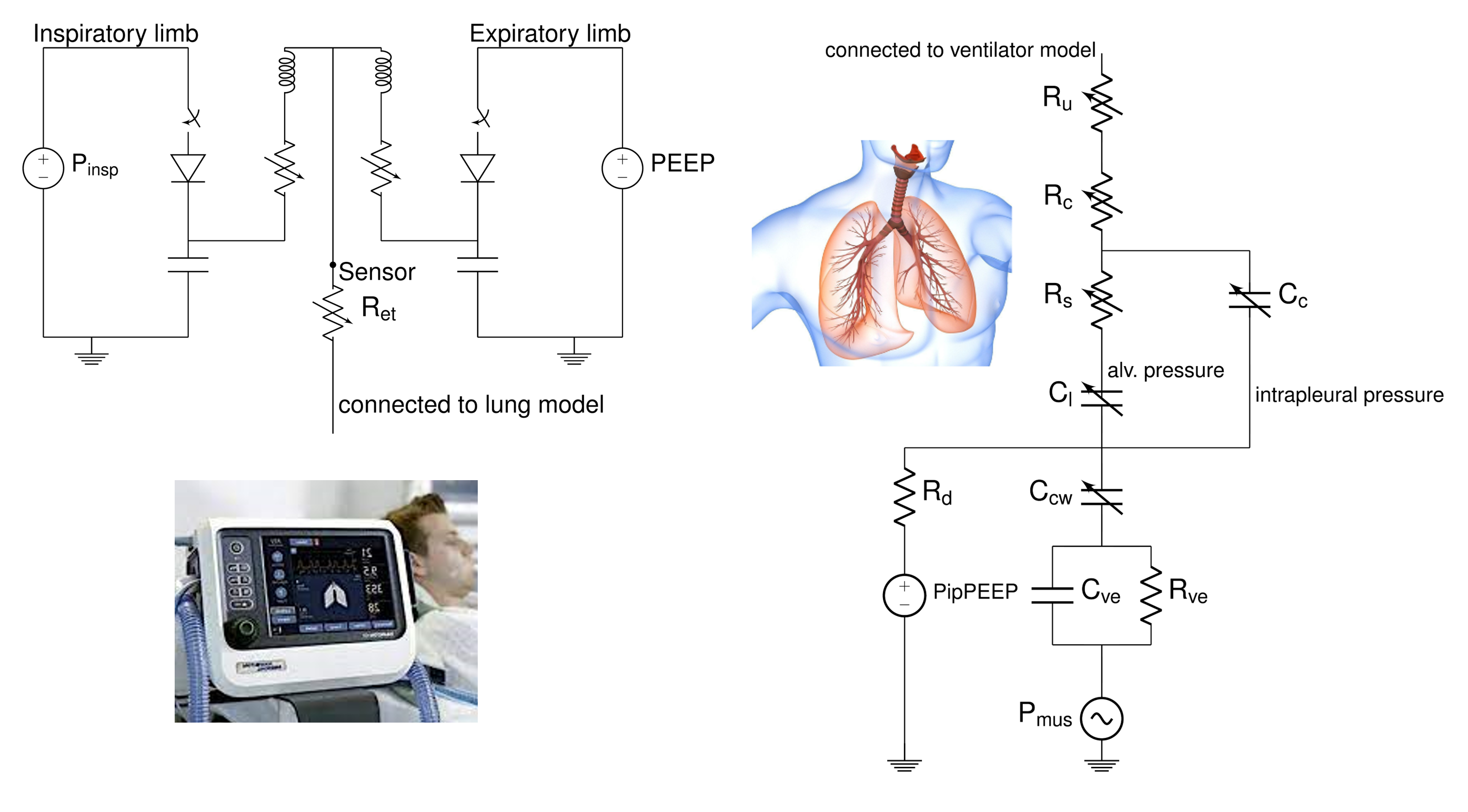

Accurate modeling of the interaction between the lungs and the mechanical ventilator is of paramount importance for better understanding of the mechanical ventilation process and the more accurate estimation of important quantities such as the patient’s work of breathing. Additionally, the occurrence of patient-ventilator asynchronies (PVAs), leading to patient discomfort, increased work of breathing and also linked to elevated mortality rates, underscores the need for real-time decision support to identify and manage these asynchronies. Motivated by this, we proposed a method for creating a large, realistic, and labeled synthetic dataset. The aim is to facilitate the training and validation of machine learning algorithms capable of detecting a wide range of asynchrony types. The approach is based on a coupled lung-ventilator model: a non-linear lung-airway model is adapted for application in a diverse patient population; additionally, a first-order ventilator model is incorporated to generate labeled pressure, flow, and volume waveforms representative of pressure support ventilation. The model successfully reproduces fundamental measured lung mechanics parameters, and experienced clinicians were unable to differentiate between the simulated waveforms and actual clinical data. This rich annotated dataset is now publicly available at https://doi.org/10.4121/81220350-0f3d-4e0a-86cf-28c904a1cb09.v1.

This sophisticated model of the lungs and ventilator is also investigated for a better estimation of patient’s respiratory efforts. In fact, although various pressure-based techniques are available for estimating inspiratory effort at the bedside, uncertainty surrounds the accuracy of their estimations. This uncertainty arises because these techniques are largely based in a simplified linear model of the respiratory system, neglecting crucial factors such as the gas compressibility of air and the viscoelasticity and nonlinearities inherent in the respiratory system. We thus performed an in-silico study to compare pressure-based estimation techniques and assess their accuracy using a more sophisticated model of the respiratory system and ventilator. The study evaluated the impact of several parameters on the accuracy of these techniques, including the patient’s respiratory mechanics, positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), inspiratory pressure of the ventilator, gas compressibility of air, viscoelasticity of the respiratory system, and the strength of inspiratory effort. We identified the whole-breath occlusion technique as the most accurate in terms of performance. It exhibited the lowest average and maximum errors across all patient archetypes. On the other hand, techniques based on esophageal pressure demonstrated errors associated with the viscoelastic element in the model, resulting in higher errors compared to occlusion-based methods. The accuracy of esophageal pressure-based techniques was found to be highly dependent on the patient’s pathology and ventilator settings, potentially evolving over time as the patient recovers or deteriorates.

Automatic detection of patient-ventilator asynchronies

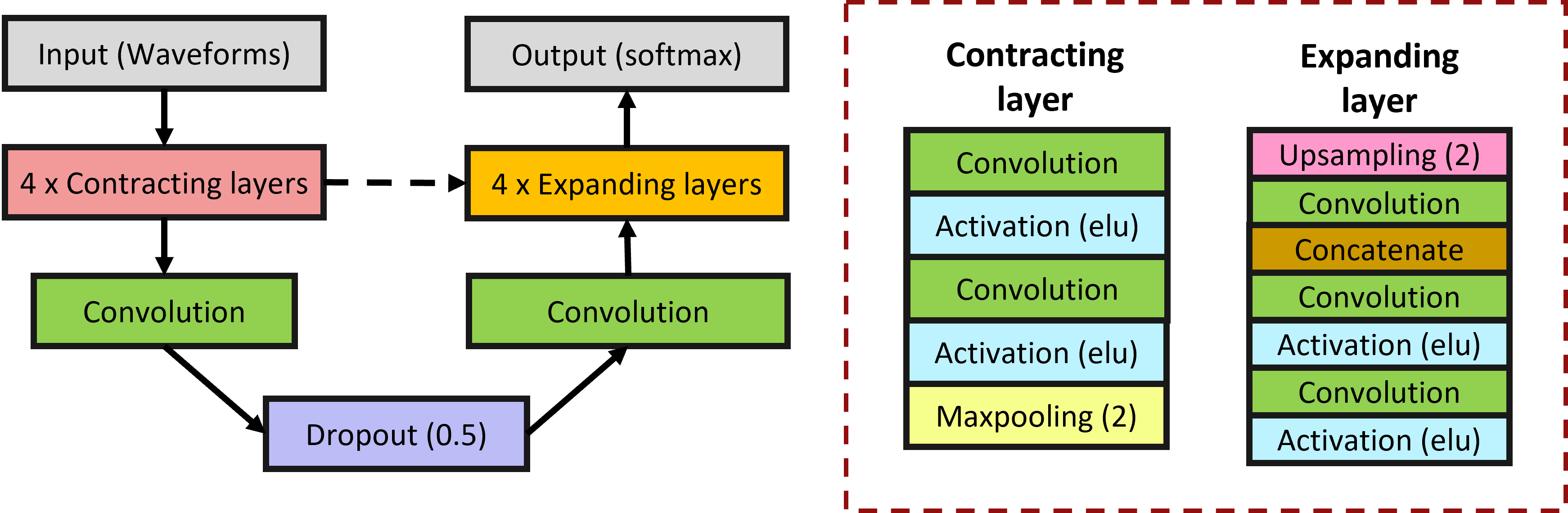

The intricate interplay between patients and mechanical ventilators in clinical settings can sometimes lead to disruptions in the synchronization of their respiratory efforts, giving rise to a phenomenon known as patient-ventilator asynchronies (PVAs). This refers to the mismatches in timing, flow, or volume coordination between a patient’s spontaneous breathing efforts and the assistance provided by the mechanical ventilator. Patient-ventilator asynchronies have attracted increasing attention within the realm of critical care, as their occurrence can have significant implications for patient outcomes. These asynchronies can compromise the effectiveness of ventilation, contribute to patient discomfort, and, in severe cases, may lead to respiratory muscle fatigue or injury. They have also been associated with increased length of ICU stay and mortality. In present clinical practice, PVAs are typically identified and explored through the visual assessment conducted by intensive care physicians. Nevertheless, this method has notable limitations. Firstly, visual inspection is time-consuming and susceptible to subjective interpretation. Secondly, maintaining continuous monitoring through visual means is impractical, potentially leading to the oversight of a significant number of PVAs. Third, accurate detection and classification of PVAs by visual analysis requires trained clinical staff. Here we propose, a machine learning approach for automatic detection and classification of PVAs . The proposed method is based on a U-net architecture, apprioprately adjusted for 1-D signals (measured pressure, flow and volume). Based on these input signals, the network learnt to recognized the start and end of patient’s respiratory efforts. Comparing these timings with the mechanical ventilator triggering and cycling, it is possible to detect and classify different PVAs. The proposed method was able to detect patient efforts with a sensitivity and precision of 98.6% and 97.3% for the inspiratory efforts, and 97.7% and 97.2% for the expiratory efforts, and demonstrated high classification accuracy (90-98%) across all types of PVAs.

To improve the model, we extended the training by using simulated data produced with the model of the lung-ventilator system explained above. We found out that the combination of simulated and clinical data for training the algorithm achieved the best performance.

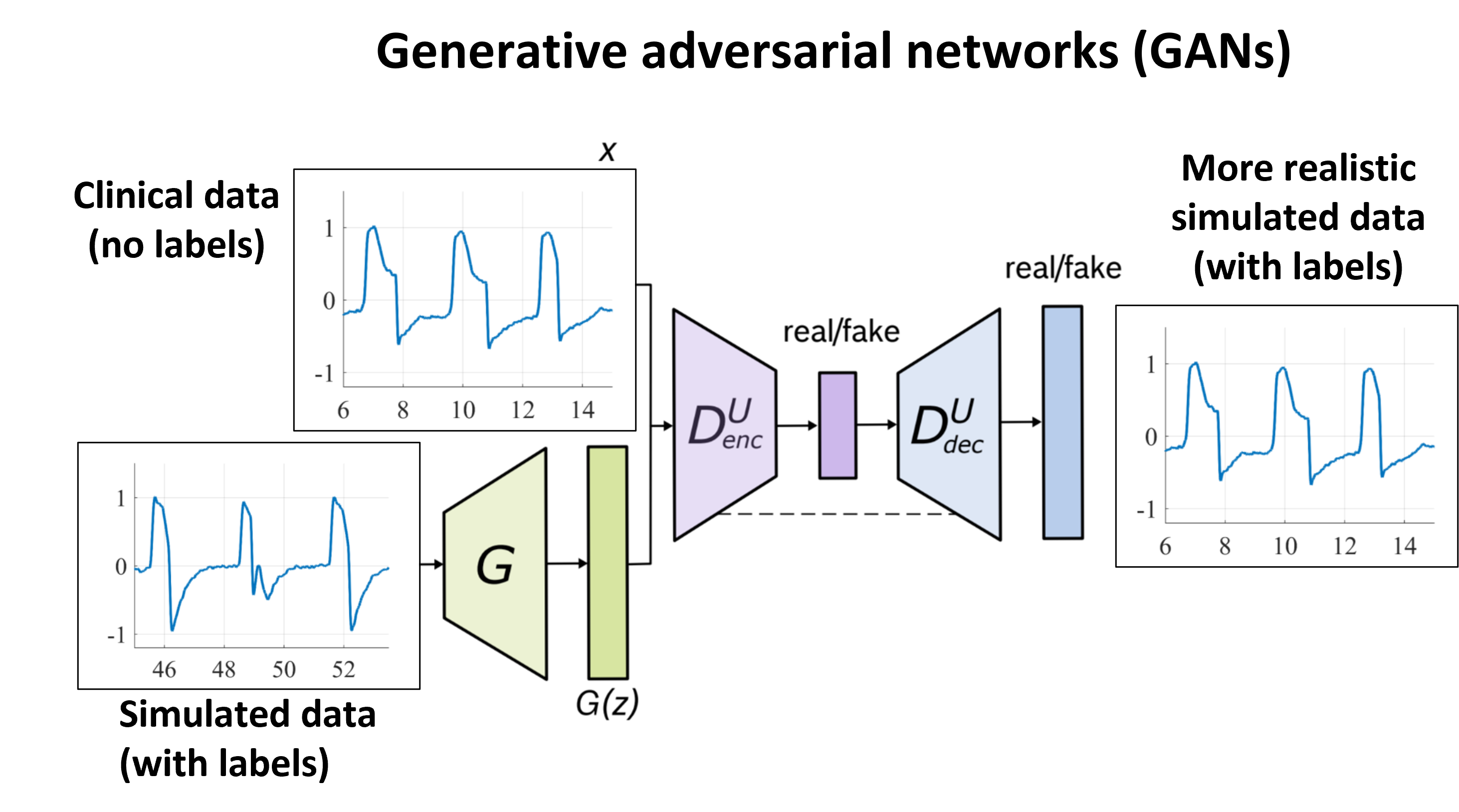

A further improvement on the detection and classification performance is obtained by refining the simulation through a generative-adversarial network (GAN) approach (VentGAN). Although clinical data with good-quality labels is scarce, large ventilation dataset are available without labels. The idea is to learn the characteristics of clinical data which cannot be modeled by the simulator through adversarial learning. By using the simulated data as input, however, we are able to maintain the known timings, and thus generate a more realistic simulated dataset with labels. The idea is summarized schematically by the picture below. With exception of ineffective efforts, we found that when using the generated data to train the above-mentioned machine learning algorithm for automatic detection and classification of PVAs, we improve both the detection and classification accuracy of all the investigated PVAs.

Contributors and partners

BM/d lab:

- Anouk van Diepen (PhD student)

- Tom Bakkes (PhD student)

- Liming Hao (former visiting PhD student)

- Nishith Chennakeshava (PhD student)

- Pierre Woerlee (part-time professor)

- Massimo Mischi (full professor, head of BM/d)

Partners:

- Catharina Ziekenhuis Eindhoven

- Policlinico S. Matteo (Pavia, Italy)

Funding:

- Eindhoven MedTech Innovation Center (e/MTIC)

- TKI-HTSM MEDICAID - Top Sector Holland High Tech

- China Scholarship Council (CSC), National Key Research and Development Project of China

- Academic Excellence Foundation of BUAA for PhD Students